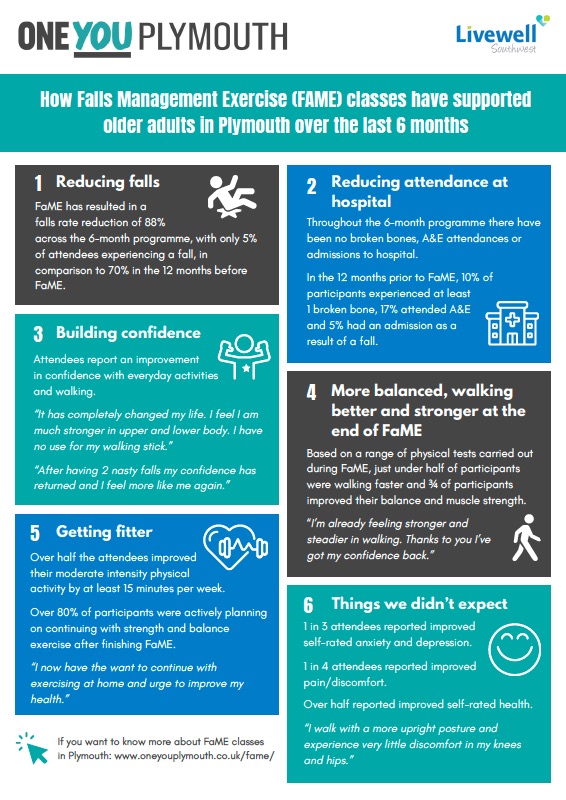

New research published this week shows that FaME sessions delivered by PSIs to the general older population through primary care (not high risk fallers) for 6 months, significantly increased habitual physical activity (self reported moderate physical activity) by 15 minutes a day even a year after the intervention finishes. These sessions also significantly reduced the risk of falls a year after the intervention finished

You can download the paper and read more about the intervention here.

This trial compared three interventions (randomly allocated) delivered to 1256 older adults (aged 65+) through general practices – FaME (PSI), Otago (OEP) and Usual Care. The older adult involved were not high risk fallers (these were sent on to falls services) but instead the general older adult population attending their GPs. The FaME group met once a week for 6 months and were encouraged to do home exercise and walking at least twice a week. The Otago group were encouraged to exercise at home for 6 months (home exercise booklet and weights) with support from peer mentors via home visits and telephone calls. The Usual Care group were just told to be more active.

The main outcome measure of this trial was the number of people increasing their physical activity towards meeting the UK Physical Activity Guidelines of at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity a week and in particular, the number who had maintained the increase in physical activity a year after the intervention stopped (follow up).

One year after the intervention stopped, the FaME group were still self reporting at least 15 minutes a day more moderate physical activity than before the intervention started. The Otago group were no more likely to have increased their activity compared to the control group (they remained with the same self reported activity levels as before the intervention started).

The secondary outcome was reported falls. At follow up one year after the intervention finished the FaME group had significantly less falls than the Otago group or the Usual Care group. There are a number of potential reasons why Otago exercises did not work in terms of primary prevention of falls in the general older population. Firstly, the intervention was 6 months long (not the 12 months reported in successful research outcomes). Secondly, the intervention support at home was provided by peer mentors (not Physiotherapists, trained nurses or specialist exercise instructors) and so this may have diluted the progression of the balance and strength exercises). Thirdly, perhaps in those who are not at high risk of falls or frailer the exercises are not sufficiently challenging to strength and balance in order to reduce the risk of future falls. However, a sub-analysis of those in the Otago arm of the trial, suggests that if they comply to at least 75% of the dose of Otago exercises (e.g.. 58.5 hours) then there is a reduction in falls one year post intervention, suggesting that perhaps if these exercises were run in groups (where compliance can be monitored and extra support given) the reduction in falls may be significant even in this low risk group.

This highlights that FaME is an evidence based intervention shown to significantly increase moderate physical activity and is also effective in the primary prevention of falls in the general population. It also highlights that Otago should be an option offered to high risk fallers only (not the general older population) if falls prevention, rather than just improvements in strength and balance, is the primary outcome.